The Indra's Net of Memories : Suh Yong-Sun's King Danjong Series

The Trace of Memories

Danjong, the sixth king of the Joseon Dynasty, was enthroned in his early teens but soon deprived of the kingship by his uncle, and then exiled to a remote region until the untimely death before his seventeenth birthday. The young king’s tragic destiny is such a pain that becomes even deeper as time goes by. It would be good if we can leave those enduring pains behind, but it is not easy to do that. Rather, it would be better to avoid the fact and pretend not to be aware of the incident. Suh Yong-Sun, however, does not avert his eyes from the history.

In 1986, Suh had an indelible experience of the tragedy of Danjong in Youngwol, the historic site of exile. Suh became curious about that there had been no art work that dealt with this historical incident and then took that as what he is destined to do—to represent the annals of King Dangjong. Since then on, for the past thirty years, Suh has been devoting himself to searching for evidences, following the traces of the young king and concentrating all his energy on making artworks of this subject. On top of it all, he has tried to express the very essence of human desire for power, brutality and fate through his art.

History is the past. It is what happened already. It is spilt milk and the words that came out of our mouth, which cannot be return to the original state. Once you have done this, you cannot restore it like new. Painting is to draw what we physically see or want to look at. However, since history can hardly be seen through our eyes, Suh could not help confronting the difficulties from the very beginning when he decided to draw the history.

Suh represents the traces and memories of the incidents surrounding Danjong, in which the figures and the places emerge as important subjects or motifs. Here we must not see his practice as that of a historian because his paintings do not merely convey the historical stories. The historians or the work of historians tell us about the past based on the historical facts, whereas Suh looks into the essence of the world through his art. In this essay, I will examine the ways in which he describes the history, focusing on some of his recent works.

Reconfiguration of the Incident

The process that had put King Danjong to death is a whole complex of diverse incidents. The visual method that Suh Yong-Sun employs is to juxtapose the incidents of different times and spaces in one scene, which reveals the historical meanings of the series of incidents. On the Way to Execution Ground (pl.1) is one of the works that show this method of representation. At first glance, we cannot easily follow the stories, yet the title helps us to understand what each scene tells and the whole picture is about—in this picture, Sayuksin (six lieges who devoted their lives for the restoration of King Danjong), who attempted to restore King Danjong to the throne, are taken to the execution ground. In the center of the picture are two cows drawing two carts upon which the convict is sitting with a pillory around his neck. On his side lied a white dead body. On the lower right side appears Kim Si-Seup as a monk, who is said to have buried those dead bodies. On the upper left corner, symmetrical opposite of the scene of Kim Si-Seup, there are the abdicated king Danjong and the queen Jeongsoon sitting on their chairs. There is a group of lieges right below them. Moving on to the upper right corner, there are several buildings of the exile site of Youngwol. It depicted a series of events starting from the movement for the restoration of King Danjong, the execution of Sayuksin, Kim Si-Seup’s taking care of the dead bodies and his becoming a Buddhist monk, and King Danjong’s being sent to exile. But here the events go back and forth different spaces from the palace, the Han River side to Youngwol. Suh employs a variety of methods to transcend the spatial-temporal difference and create coherent visuality; first, he inserts a long flow of blue river that crosses the whole picture plane diagonally; the river starts from Dong-gang river in Youngwol, converges with the South of Han River, and flows out into Noryangjin again; second, he illustrates all the characters, except the convict, the King and the queen, as keeping upright postures; third, chromatically, he repeats blue, red and green, by which he expresses rhythmic visual coherency.

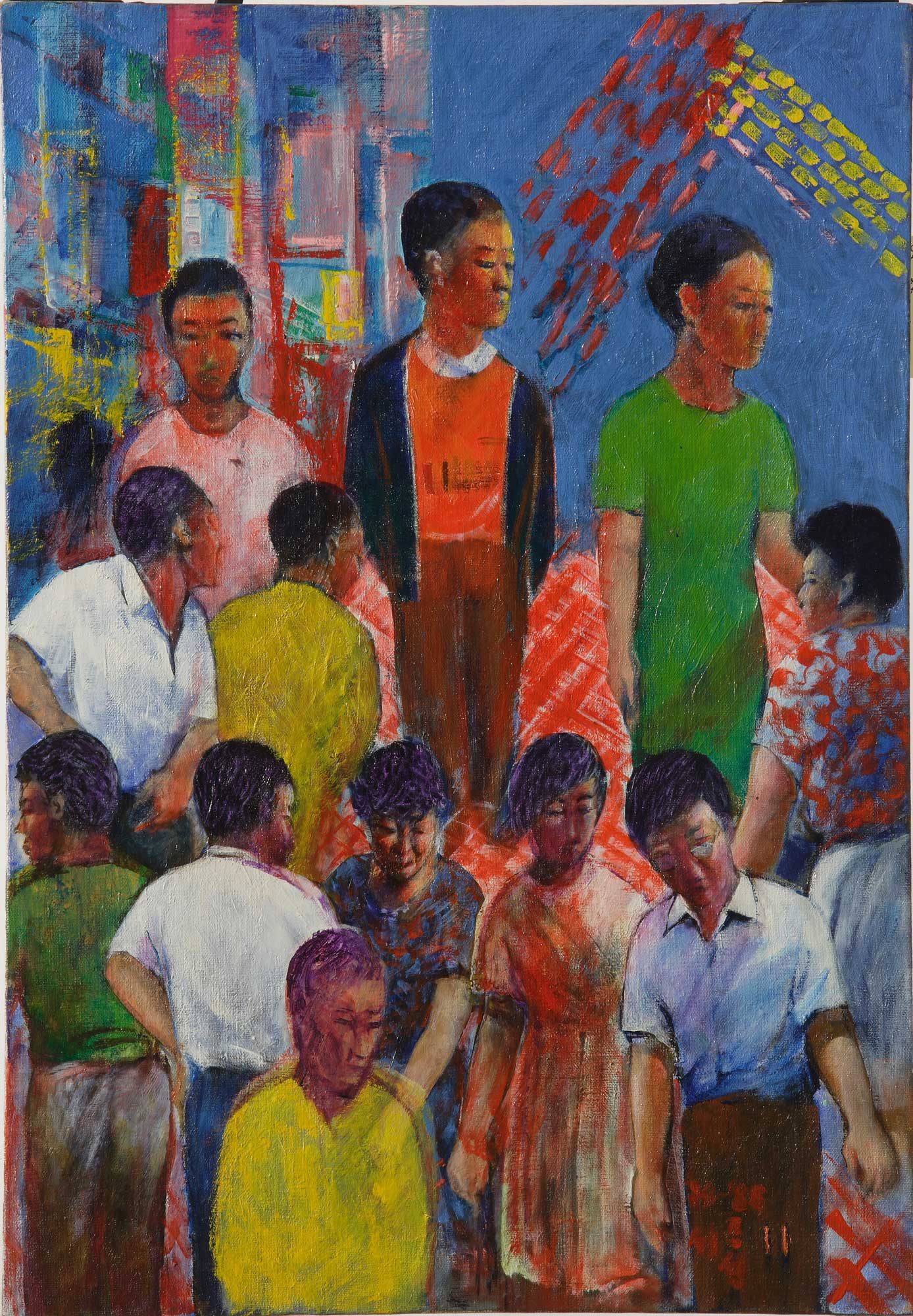

Thoughts of the People – Queen Jeongsoon (pl.2) visualizes the history in the similar way. The abdicated and exiled King Danjong in red royal robe is standing on the right, while a woman, the queen, standing on her back to the king. It is when the queen Jeongsoon lived in a modest small thatched-roof house outside Dongdaemun gate (outside the capital city), while her husband being exiled in the far remote region. This scene shows the women in the village helping the queen’s humble living. The people in farmers’ outfit are strolling around the furrows. In this case, the people of similar postures and the close inter-relation among them tie the different incidents in the picture with one another.

Suh also utilizes the method of editing; dividing the picture plane and arrange several incidents inside each section. In the center of the King Danjong and the Queen (pl.3), the abdicated king and the queen stand face to face with King Sejo who took the throne. Here, Sejo shows his back, whereas he reveals his face on the upper left section of the picture. Right below it are the Sayuksin in the prison waiting to be killed by Sejo. Upper right corner shows the landscape of Youngwol and below this scene is Kim Si-Seup on the road to somewhere. The individual incident is located in the sectional frame reminds of the comic strips Ahnpyeong, Donghak-sa (pl.4) is about the gye-yu-jeongnan (a purge brought up by Prince Suyang, later King Sejo, to take the throne) and Prince Ahnpyeong (the brother and rival of Prince Suyang). King Sejo in the royal robe and his clique standing in the center stage are plotting to rise a revolt, while at the bottom, Jong-Suh Kim, the supporter of Danjong is passing by on the horse. Upper left corner is Ahn Gyeon who is painting the masterpiece titled A Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Spring Land in the house of Prince Ahnpyeong. On the mid-right side of the picture, Kim Si-Seup is sitting on the ground in the feature of a monk, while the landscape of Donghak-sa temple of Gyeryong mountain is unfolding in his below. As in other paintings, the formal regularity of the roof tiles and color planes of stark contrast link individual events as one entity.

The artist juxtaposes different spaces and different times in one picture as those small events are all closely related to one another. The people who are involved in the incident appear in one picture regardless of their actual locations and temporal differences. There happened so many events within a short period of time between the 1453 Coup and the death of King Danjong. Only after his death, fragmented memories of those events began to come up little by little in Youngwol. Suh builds up one historic scene by criss-crossing the events dialectically.

Conjuring Up the Figure

For Suh Yong-Sun, King Danjong is the true source of elegy. In his pictures, King Danjong appears as a little king, impotent abdicated king, exiled Prince Nosan (the dethroned name of King Danjong) and a dead boy in the freezing cold river in Youngwol. Danjong became a prey for his uncle’s ambition, a missing and yearning love in the queen’s heart, and the remorse to his loyal supporter Kim Si-Seup. That is why he is depicted as a little boy in red royal robe with no beard. Mostly Danjong has no expression on his face, yet sometimes the artist describes him quite roughly and reveals the inner fury of the little king. We can compare this with the Portrait of Danjong (pl.5) painted by Gi-Chang Kim, which is based on a royal fable; when King Danjong was exiled in Youngwol, a scholar named Ik-han Chu often presented him with wild grapes. One day, on his way to Taebaek mountain, Chu met King Danjong on a white horse, wearing royal robe and winged cap on his head. But, when Chu arrived in his place in Youngwol, he found the king dead already. What Chu saw on the road was the ghost of the king. Based on this story, Gi-chang Kim described Danjong in peace with no further pain, as he regarded the king as a spirit that had left this world. Compared to this, Suh’s illustration of Danjong is nothing but scary.

Beside King Danjong often appears the Queen Jeongsoon. She got married to the king at the age of 15, lost her husband at 18, and lived for another 65 as a widow until she died at 82. When the king was sent to exile, her status was degraded to layman and she lived in a small thatched-roof house outside Dongdaemun gate – little trace of the queen is left there now. Often in Suh’s picture, the queen is depicted along with the king, relying upon each other in the bloody dark turmoil of the palace. Even when the king was exiled, being separated apart, they were featured to have had a connection by the heart. In the picture titled Queen Jeongsoon (pl.6), King Danjong is looking at the Donggang river and the queen Jeongsoon appears inside the building in Youngwol. The intense longing for her husband seems to have her incarnate as a fantasy like this.

King Sejo, who caused the tragedy of King Danjong, often appears in the picture, too. Strangely, however, King Sejo looks almost the same as King Danjong except a little bit older look on his face – it is due to the elimination of expressions and the characters of the figure. There is no portrait of King Sejo left now. When Suh was in New York, he drew the face of King Sejo on an ad flier (pl.7), based on the image that he found on the internet which was an imagined portrait illustration in Seonwon bogam published in the 20th century. Suh reused a telecommunication company’s advertisement flier with Spanish letters on it, put a cut of the foil bag of instant noodle on the face of King Sejo in order to portray the atrocious disposition of the character.

During Joseon Dynasty, the royal portrait of King Sejo was enshrined in Bongseon-sa temple near his tomb. It was one of the two royal portraits – along with the portrait of King Taejo – that were preserved during the Japanese Invasion of Korea. After the war, the portrait of King Sejo had been enshrined in the royal portrait hall in the capital and removed to Busan during the Korean War. Unfortunately, however, it was lost by the fire in 1954. Interestingly, there is a photograph of his royal portrait. We can have a glimpse of King Sejo in the picture of a painter Eun-ho Kim copying the portrait of King Sejo in 1928 (pl.8). It is ironic that the more we try to erase the look of Sejo, the more indelible it becomes. Suh is contributing to this paradoxical persistence as well.

Another figure that often appears in Suh’s picture is Kim Si-Seup. From the early age, he was known to be a genius scholar but he became a monk due to the rage against Sejo’s usurpation of kingship. Kim Si-Seup wandered around across the country while leaving the stories of King Danjong and Sayuksin in many different regions. In Suh’s picture, Kim Si-Seup is depicted in the feature of monk, with skin head and in Buddhist garb. The Throne: King Danjong and Suyang (pl.10) illustrates the faces of Sejo and Kim Si-Seup as if they were the sun and the moon. It seems an analogy of their uncompromising relationship to the contrast between the sun and the moon. His portrait remains in Muryang-sa temple where he spent his later years. (pl.11) To Suh, who searches every nook and cranny about Danjong, the portrait of Kim Si-Seup – presumed to be a self portrait – means truly something. He visited the temple to look at the work in person and used that image in his own work as well. Meanwhile, that is not probably a self-portrait, but seems tobe a portrait emulated by the later generation. The original feature and the true thoughts and mind of Kim Si-Seup still remain ambiguous.

A new figure in this series is the painter of Joseon Dynasty named Ahn Gyeon. In fact, he has no direct relationship with King Danjong. Ahn Gyeon was chosen by the artist’s personal interest in the painter and his historic piece; in 1447, Prince Ahnpyeong, the third son of King Sejong, dreamt about the paradise of peach garden. He then let a renowned painter Ahn Geon visualize his dream, which became the famous Mongyudowondo (pl.12). Upon this work, over twenty poems had been written by the people who later became involved with the tragedy during the the 1453 Coup and with the restoration of King Danjong. In Ahnpyeong-Donghak-sa appears Ahn Gyeon himself painting; in front of him lies the work A Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Spring Land depicted exactly as same as the original piece. Such a hyper-realistic illustration of objects is rare among Suh’s works. This ‘picture within the picture’ gives rise to a sort of confusion—the beautiful peach flavour of the garden of fantasy seems an omen prior to the bloody turmoil. As events are what people bring about, Suh often represents the incidents surrounding King Danjong through diverse yet specific figures involved with each event. For that reason, Suh calls upon a variety of historical figures. Some figures simply look at what happens to themselves, which shows that they had no choice but to observe what was happening with frustrating feelings. Sometimes the same figure appears twice or even three times in one picture. It may cause a sense of embarrassment as if we encountered ourselves in a dream. It applies to the figures other than the protagonist of the picture. They are often just standing in a rigid posture—in front of such a desperate moment to be dead or alive, they are not even agitated. Why aren’t they? Are they not human beings but ghosts?

The Representation of Place

Suh Yong-Sun believes that events are inseparable from space and history is tied to the place. That is why he himself visits the historic places and makes sketches on site. Of all other places, Youngwol where King Danjong faced his death, means to him the most. King Danjong actually stayed in Youngwol only for five months. He was at age seventeen then. King Danjong spent most of his short life inside

the palace but every single trace of him in the palace had been erased. Only after two hundred years since his death, he could be restored in history as a king. Yet still, what have left about him are just vague memories and a small tomb of him. Instead, even more legends and unofficial fables about him have been spread out. Suh has painted particularly many scenes of Cheongryeongpo in Youngwol where King Danjong was exiled, died and buried because this is one of the rare tangible entities related to the tragic king. Meanwhile, figures appear in different forms and looks even in the samelocation. In previous works, Cheongryeongpo used to be composed of mountains and rivers of the region depicted as wide color planes, whereas in Cheongryeongpo (pl.13) Suh expressed the place in a more rough way to represent changed point of view. As such, even the same place comes in different forms depending on the viewer’s perspective. You can see the place of Prince Ahnpyeong in the picture of Ahnpyeong-Donghak-sa. Recently in Ok-in-dong located in Seoul, an old stone bridge was discovered, which is presumed to be in the house of Prince Ahnpyeong. Suh, focusing on this bridge, created Bihae-dang (pl.14). Jung Sun, a renowned painter of late Joseon Dynasty, painted the same stone bridge in his work titled Suseong-dong. Suh believes that Jung Sun also painted this landscape with an acknowledgement of the tragic incident that had happened there (pl.15). With this small stone bridge, the artist creates a connection from Prince Ahnpyeong, Ahn Gyeon and to King Danjong,You can find a similar case in the landscape Gyeongja(Respect) Rock (pl.16) hich is deeply involved with King Danjong. On a large rock in the stream that flows by the Sosu School in Soonheung, there is an inscription of a letter ‘Gyeong’(敬 Respect). Soonheung is the place where Prince Geumsung, a younger brother of King Sejo, was exiled. Prince Geumsung was executed for plotting to restore King Danjong together with many Soonheung local people. It is said that there was a boisterous cries of the ghosts afterwards, and the sound stopped when Se-Boong Joo (who built sosuseowon) put red paint on the letters as a sign of consolation. Here, a letter inscribed on a stone of a stream pull out the tragic stories of Danjong.

Besides them, Suh painted many difference places where he could find the traces of Sejo. Among other places, Donghak-sa in Gyeryong-san mountain has a particular meaning to the artist. Kim Si-Seup held a memorial service for Sayuksin and Sejo himself visited the site and ordered to build a gazebo as a memorial to 280people killed by him. A documentary film titled Invocation of the Spirit of the Dead, directed by Lim Hong includes a scene where Suh visits Donghak-sa, finds Kim Si-Seup’s ancestral tablet among dozens of them, and opens up to look at the mortuary tablet. It is a shivering and creepy moment as if he were searching for a ghost spirit. As such Suh has been tracing the vestiges of the people who had been involved with the abdication and the death of King Danjong, and recording the stories into his paintings.

The Indra’s Net

Suh Yong-Sun has found many things surrounding the tragedy of King Danjong for a long period of time. Ironically, however, the more facts are found and added, the more the story becomes distanced apart from the truth. Putting small pieces together does not guarantee the restoration of the original shape. When one fact is combined with another fact, it may change the whole picture of the event. When one figure makes relationship with another person, it could change one’s own feature as well.

Suh recomposes the incidents, calls upon some of the important figures, and represents the specific places in order to describe the stories of King Danjong as realistic as possible. His goal is not the restoration of history. For Gerhard Richter who took Red Army Faction as a motif of his work, the subject of the work was not ideology or violence but artistic practice regarding the issues of art itself. The same is true with the art of Suh. His work is ultimately not about history but about the relationship between people, which reminds of the Indra’s net of Buddhism. Indra is an ancient god of India, whose palace is covered with a net of transparent beads. A plethora of transparent beads studded on each joint of the net reflect all things in heaven and earth and they are mirroring to one another. It is like a Buddhist law of cause and effect; or, all the phenomena in the universe hold one’s own completion in them, yet they can exist only in relationships with others. These phenomena, like the transparent beads, reflect the lights to one another and create a big whole. In this sense, here is an analogy between the art of Suh and the Indra’s net of the Avatamska Sutra.

Suh does not only depicts the stories of King Danjong but deals with the reality of the past and the present. Whether they are the people around King Danjong or the grass roots of the Korean War, or the miners of Cheol-am, or the citizens of Beijing, Melbourn or New York, they all reveal the complexities of human relationship and of the world. What Suh is obsessed about is life and death of human beings, moments and eternity of time, continuity and disconnection of space. Numerous events, figures and places reflecting one another make even brighter light and then disappear by being buried with the light. In this way, the works of Suh represent the world of Avatamska where things become the Indra’s net and sublimate to a constellation of flowers.

Another figure that often appears in Suh’s picture is Kim Si-Seup. From the early age, he was known to be a genius scholar but he became a monk due to the rage against Sejo’s usurpation of kingship. Kim Si-Seup wandered around across the country while leaving the stories of King Danjong and Sayuksin in many different regions. In Suh’s picture, Kim Si-Seup is depicted in the feature of monk, with skin head and in Buddhist garb. The Throne: King Danjong and Suyang (pl.10) illustrates the faces of Sejo and Kim Si-Seup as if they were the sun and the moon. It seems an analogy of their uncompromising relationship to the contrast between the sun and the moon. His portrait remains in Muryang-sa temple where he spent his later years. (pl.11) To Suh, who searches every nook and cranny about Danjong, the portrait of Kim Si-Seup – presumed to be a self portrait – means truly something. He visited the temple to look at the work in person and used that image in his own work as well. Meanwhile, that is not probably a self-portrait, but seems tobe a portrait emulated by the later generation. The original feature and the true thoughts and mind of Kim Si-Seup still remain ambiguous.

A new figure in this series is the painter of Joseon Dynasty named Ahn Gyeon. In fact, he has no direct relationship with King Danjong. Ahn Gyeon was chosen by the artist’s personal interest in the painter and his historic piece; in 1447, Prince Ahnpyeong, the third son of King Sejong, dreamt about the paradise of peach garden. He then let a renowned painter Ahn Geon visualize his dream, which became the famous Mongyudowondo (pl.12). Upon this work, over twenty poems had been written by the people who later became involved with the tragedy during the the 1453 Coup and with the restoration of King Danjong. In Ahnpyeong-Donghak-sa appears Ahn Gyeon himself painting; in front of him lies the work A Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Spring Land depicted exactly as same as the original piece. Such a hyper-realistic illustration of objects is rare among Suh’s works. This ‘picture within the picture’ gives rise to a sort of confusion—the beautiful peach flavour of the garden of fantasy seems an omen prior to the bloody turmoil. As events are what people bring about, Suh often represents the incidents surrounding King Danjong through diverse yet specific figures involved with each event. For that reason, Suh calls upon a variety of historical figures. Some figures simply look at what happens to themselves, which shows that they had no choice but to observe what was happening with frustrating feelings. Sometimes the same figure appears twice or even three times in one picture. It may cause a sense of embarrassment as if we encountered ourselves in a dream. It applies to the figures other than the protagonist of the picture. They are often just standing in a rigid posture—in front of such a desperate moment to be dead or alive, they are not even agitated. Why aren’t they? Are they not human beings but ghosts?

The Representation of Place

Suh Yong-Sun believes that events are inseparable from space and history is tied to the place. That is why he himself visits the historic places and makes sketches on site. Of all other places, Youngwol where King Danjong faced his death, means to him the most. King Danjong actually stayed in Youngwol only for five months. He was at age seventeen then. King Danjong spent most of his short life inside

the palace but every single trace of him in the palace had been erased. Only after two hundred years since his death, he could be restored in history as a king. Yet still, what have left about him are just vague memories and a small tomb of him. Instead, even more legends and unofficial fables about him have been spread out. Suh has painted particularly many scenes of Cheongryeongpo in Youngwol where King Danjong was exiled, died and buried because this is one of the rare tangible entities related to the tragic king. Meanwhile, figures appear in different forms and looks even in the samelocation. In previous works, Cheongryeongpo used to be composed of mountains and rivers of the region depicted as wide color planes, whereas in Cheongryeongpo (pl.13) Suh expressed the place in a more rough way to represent changed point of view. As such, even the same place comes in different forms depending on the viewer’s perspective. You can see the place of Prince Ahnpyeong in the picture of Ahnpyeong-Donghak-sa. Recently in Ok-in-dong located in Seoul, an old stone bridge was discovered, which is presumed to be in the house of Prince Ahnpyeong. Suh, focusing on this bridge, created Bihae-dang (pl.14). Jung Sun, a renowned painter of late Joseon Dynasty, painted the same stone bridge in his work titled Suseong-dong. Suh believes that Jung Sun also painted this landscape with an acknowledgement of the tragic incident that had happened there (pl.15). With this small stone bridge, the artist creates a connection from Prince Ahnpyeong, Ahn Gyeon and to King Danjong,You can find a similar case in the landscape Gyeongja(Respect) Rock (pl.16) hich is deeply involved with King Danjong. On a large rock in the stream that flows by the Sosu School in Soonheung, there is an inscription of a letter ‘Gyeong’(敬 Respect). Soonheung is the place where Prince Geumsung, a younger brother of King Sejo, was exiled. Prince Geumsung was executed for plotting to restore King Danjong together with many Soonheung local people. It is said that there was a boisterous cries of the ghosts afterwards, and the sound stopped when Se-Boong Joo (who built sosuseowon) put red paint on the letters as a sign of consolation. Here, a letter inscribed on a stone of a stream pull out the tragic stories of Danjong.

Besides them, Suh painted many difference places where he could find the traces of Sejo. Among other places, Donghak-sa in Gyeryong-san mountain has a particular meaning to the artist. Kim Si-Seup held a memorial service for Sayuksin and Sejo himself visited the site and ordered to build a gazebo as a memorial to 280people killed by him. A documentary film titled Invocation of the Spirit of the Dead, directed by Lim Hong includes a scene where Suh visits Donghak-sa, finds Kim Si-Seup’s ancestral tablet among dozens of them, and opens up to look at the mortuary tablet. It is a shivering and creepy moment as if he were searching for a ghost spirit. As such Suh has been tracing the vestiges of the people who had been involved with the abdication and the death of King Danjong, and recording the stories into his paintings.

The Indra’s Net

Suh Yong-Sun has found many things surrounding the tragedy of King Danjong for a long period of time. Ironically, however, the more facts are found and added, the more the story becomes distanced apart from the truth. Putting small pieces together does not guarantee the restoration of the original shape. When one fact is combined with another fact, it may change the whole picture of the event. When one figure makes relationship with another person, it could change one’s own feature as well.

Suh recomposes the incidents, calls upon some of the important figures, and represents the specific places in order to describe the stories of King Danjong as realistic as possible. His goal is not the restoration of history. For Gerhard Richter who took Red Army Faction as a motif of his work, the subject of the work was not ideology or violence but artistic practice regarding the issues of art itself. The same is true with the art of Suh. His work is ultimately not about history but about the relationship between people, which reminds of the Indra’s net of Buddhism. Indra is an ancient god of India, whose palace is covered with a net of transparent beads. A plethora of transparent beads studded on each joint of the net reflect all things in heaven and earth and they are mirroring to one another. It is like a Buddhist law of cause and effect; or, all the phenomena in the universe hold one’s own completion in them, yet they can exist only in relationships with others. These phenomena, like the transparent beads, reflect the lights to one another and create a big whole. In this sense, here is an analogy between the art of Suh and the Indra’s net of the Avatamska Sutra.

Suh does not only depicts the stories of King Danjong but deals with the reality of the past and the present. Whether they are the people around King Danjong or the grass roots of the Korean War, or the miners of Cheol-am, or the citizens of Beijing, Melbourn or New York, they all reveal the complexities of human relationship and of the world. What Suh is obsessed about is life and death of human beings, moments and eternity of time, continuity and disconnection of space. Numerous events, figures and places reflecting one another make even brighter light and then disappear by being buried with the light. In this way, the works of Suh represent the world of Avatamska where things become the Indra’s net and sublimate to a constellation of flowers.

Insoo Cho (Professor at Korea National University of Arts)

Gaze of Politics

Recently Suh Yongsun is very active in producing paintings. It is possibly because he retired from teaching and now enjoys more freedom. Anyhow, he is expanding his eyes as an artist, frequently traveling the United States, China and Japan back and forth. Yet, the objects with his gaze on and the subjects in his focus are still affairs of ordinary people. A variety of scenes made by people in the world, if I may call it this way. Suh constantly speaks about his interests in people.

Is there a single thing that is done by a human yet not political? The same applies to Suh Yongsun’s works. Suh turns his eyes here and there, and they become art works, implying some political messages to us. Maybe the messages themselves don’t maintain specific political motivation. However, the people and the cities that he painted, or the scenes-the mixture of people and cities-have power to catch our own eyes. They are also full of suggestions as if they wanted to deliver certain political messages, albeit unclear ones, to us.

The artist who used to show stark and mechancal urban scenes, and create historical and political scenes related to King Danjong, now turns his eyes to overseas. He paints the people and scenes of specific places that he stays into produce art pieces, and by doing so, he displays much deeper and varied gazes. The scenes in his paintings, for example, the cafes, streets in Melbourne and subways in Manhattan, NewYork, are very political. Manhattan, a city of capitalism in the extreme, is a spectacle urban area with both illusion and existence, where people from everywhere gather and dream all sorts of dreams, and it is thus full of desire. The scenes of Berlin, which holds significance to us as a symbol of division, are no less political. It I an urban area with history and politics of which the division between the east and the west, and the subsequent control and suppression are stil fresh in our memories.

There’s no way for us to know if the artist has any political views or beliefs. And we don’t meed to. Notwithstanding, we can ask questions to ourselves when we face his works. Different regions, cultures and emotions maybe. But the faces of various lives of people who carry their daily lives in each city, or even subway stations and buildings of division have faces that have been together with the history. Suh tries to depict these faces with painting. The people and scenes that he looked at as an alien are not just objects of his interests. They contain politics of existence and history. And the artist wants these to be implies in his paintings. Hence, Suh’s works are of the humanities. He talks about the humanities not with language but with visual images. The narratives are, in the end, the artist’s gaze upon ‘human’.

Everything including institution, custom, borders,cities, production and consumption forms the scenes of the time, but the subject is always’humans’. From this perspective as well, Suh’s paintings are very much of the humaities.

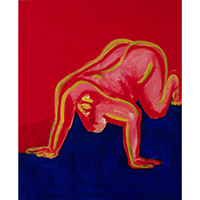

At the same times, it is his own gaze into ‘himself’. A series of his self-portraits including ,is the process to show that the artist is also a part of the ‘humans’. Thus, there is heightened tension between the external and internal, surrounding his identity as an artist. He is described like a beast with expressionistic tradition and sentiment, and it is a strategy to maximize this collision and tension. Perhaps he is throwing the ultimate and fatalistic question to himself as a painter-“What is it to paint?”And there’s no answer to all of these. We are only to live in a reality of existence and situation. Whether it is New York, Berlin or Seoul, there’s just a slight difference in existence and situation. We eat in restaurants, drink tea in cafes, buy cakes and take subways to home. As we are not aware of the politics in such scenes, another day passes by and tomorrow that is just like today comes.

YoungMok Jung(professor at Seoul Natioanl university)

Utopia’s Delay-The Painter and the Metropolis

“Utopia’s Delay: the Painter and the Metropolis” focuses on the theme of city dwellers and its landscape(/cityscape) among many other themes that he has been working on for 7 to 8 years since his exhibition in 2007.

“Utopia’s Delay: the Painter and the Metropolis” is yet another museum quality solo exhibition by artist Suh Yongsun. Suh’s previous exhibitions include “Memory, Representation: Suh Yongsun with 6.25” at Korea University Museum, “Historical Imagination: The King Danjong Stories by Suh Yongsun” at White Block in Paju, Korea, “ARS ACTIVA 2014_Arts & Their Communities” at Gangneung Museum of Art, and “The 26th Lee Jung-seob Art Award winner exhibition, Suh Yongsun’s Heterotopia: the Forfeiture of Myth” at the Chosun Ilbo Museum of Art.

As if it was planned, the series of exhibitions display the images of the Korean War, historical tragedies, myths, landscape and cityscape, all of which intricately highlights his world of art. Of course, this does not convey the entire world Suh has experienced. From self-portraits, which he has worked on in his whole career, paintings of the abandoned mine town Cheol-am, that he has persisted on for nearly 15 years, and to new paintings of Bukchon, which he started in recent years – these artistic steps are diverse and there are still more themes that Suh has not introduced in his exhibitions yet. However, it is remarkable that one artist has produced several quality exhibitions in a short span of 2 to 3 years. This may suggest that his world of art is ‘problematic,’ but such controversy itself is unprecedented in our history of art.

I

The City series, a fundamental interest of Suh, is the latest theme focused on in his exhibition. He started working with the city theme early on and even made his art world debut with his city paintings. During when Suh was gaining attention from his Pine Tree series, Suh introduced his city dweller portraits as a part of his first solo exhibition in 1980s - a task Suh has worked on since his early years as an artist.

Ihn Bum Lee (Professor at Sangmyung University, Visiting professor at Free University of Berlin)

It is not certain whether his interest was rooted in a longing for a city life or an uncomfortable perspective towards it, but few paintings that he made in the 1970s including Men with Necktie series could be regarded as one of his city paintings. This may be a natural sequence. Growing up in the Miari border zone on the outskirts of Seoul, there were many stories about the war, as the war had demolished or broken everything. For Suh, painting itself may have been the commencement of reality. Whether it was an expression of conflict or an attempt for reconciliation, making paintings that demonstrate such images and configurations was not easy for Suh, especially when the ‘white monochrome’ dominated the Korean art market and became an aesthetic order and standard in academics as well.

What is clear is that Suh Yongsun has never ceased to paint cities. Cities are what started and continues in his paintings. There is no exception when he traces back to the political tragedies of Nosangun or when he goes deep into landscapes of Jirisan or Odaesan. The city is a place that he has to stand upon whether or not he wants to. In such aspect, it is not an exaggeration to say that city life was the birth point of his artistic will. The city is an object of motivation for Suh.

His attitude as an artist towards the reality of the city may have been interpreted as disturbing and ideological during the politically and socially turbulent time in the 1980s. In the 1990s when the expansion of the city of Seoul reached the limit, his work explored individualized and isolated loss of human nature.

II

To what extent have Suh Yongsun’s city drawings reached today? Where is it heading?

From this exhibition, it is noticeable that cities are not geologically limited to Seoul, the city where he was born and eventually settled in. The metropolis-scape and people living within expanded to cities that include New York, Berlin, Beijing, Tokyo and Melbourne. Suh stayed in each of these cities numerous times varying in time from a few years to 5 to 6 months.

Suh’s interest in humanities and imagination is more extensive than anyone. However, it is hard to read or catch such narratives from his cityscapes. There is no conceptual approach or traces of intellectual examination. It is not even a literary report on urban life or interest in touristic leisure and folklore. Furthermore, in this series, the indication of isolation and loneliness that we could have found from the Seoul landscape is missing. Then, where does this aesthetical persuasion or humanitarian/social voice coming from?

There are noticeable differences in time periods, but it is not hard to find a com-

mon mysterious aura emitted from Suh’s city paintings. This energy not only operates in the global world as one huge market, but it also conditions our lives. His city drawing is about the landscape and the people within, but the keen perspective of the artist towards an invisible power across the landscapes and people, captures the viewer’s attention. Sometimes this spirit approaches the viewer with an expressive touch and vivid colors and other times with composition and order. Something that crosses the so-called globalized capitalistic system does not differ much from how they appear as the evidence of truth in front of us or as rational documents that cannot be denied or through the artist’s physical experiences. Each part of the city remains as material evidence by the artist’s hand. Systemized by the capitalistic market mechanism, people in cities and the world get distracted by capital and stock market or turn their attention to the surreal landscape of J. Baudriallard’s term: ‘symbol-image, media.’

These works are different from just a simple city anthem or emotional judgment or social critique. To an ordinary person, despite living in extremely abstracted transportation, communication and monetary systems, we cannot explicitly explain or sense it, but we continue to live in this system anyhow. Suh’s works inform us how much our everyday lives are careless and nonessential. Each work shows us the gap between the utopia that we dream of, living in such cities in reality. Therefore, we can be aware of where we are between utopia and reality. It may look or sound expressful from a cursory glance; however, people and landscapes that Suh ran into are depicted neutrally or without judgment. It looks like the reality of city life or the mechanism that operates in the background are exposing themselves and are showing the truth rather than emotional or subjective judgment of taste. In this point of view, Suh’s city drawing does not engage much in acumen but exposes his skin and body to the world through his artworks.

Now Suh’s city drawings seem to possess an air of cumulated insight toward the inlayers of life or experiences of reality. From the Pine Tree series, historical theme including the Diaries of Nosangun, tragedies of Korean War, myths or landscapes, Cheol-am drawings and experiences that he gained through art community movement and Baekryungdo projects. Therefore, the reason why the exhibition, , is not interpreted as one-sided on the engagement with the reality or political and social environment is not just because of the ambiance of the era

III

Recently, the artist’s interests are focused towards a city where people can dream about happiness. The city is depicted as an unavoidable site in the global world where human beings are bound together by a common destiny. Despite often being a topic of interest to us, cities often lead us to an uncomfortable and unstable world. Most often, those cities are unstable and guide us to crisis or tension.

However, are Suh’s interpretations of landscapes provable without including the desire to live together? The power that makes us confront the reality or truth comes from his interpretation by asking fundamental questions such as: What is the meaning of life? How do human beings exist? Suh’s artworks are aimed towards people who reside in cities, people who relinquished to live poetically, but at the same time, people oblivious to their existence. Therefore, Suh’s city drawing paradoxically changes dreaming about a happy community to aesthetical desire. Like Heidegger once said, Suh’s city drawings are an exploration of the methods to “residing poetically” and finding “the way to write poems contemplating through ones who are going to die” by “accepting one’s nature”.

Recently he is returning to history and the place where he was born and raised. He explores Seochon, the western foot of Inwangsan and Bugaksan where Anpyeong Deagun in early-Joseon period and Kyumje Jeongsun in mid-Joseon period resided. His wish to live together as a community spatio-temporarily continues even today.

If the exhibition of “The Artist of the Year 2009” by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art was an introduction, several museum quality exhibitions of Suh in recent years can be seen as the details. This may not have been possible without his works’ rich possibilities for interpretation and extensive amount of work. “From pine trees to his numerous self-portraits, historic figures like Kim Siseup, King Danjong, Um Heungdo, King Sejo, Kim Jongsuh, warriors that composite the tragedy of the Korean War like Stalin, Churchill, McArthur, and numbers of grass roots that suffered without knowing reasons… people living contemporarily in the landscapes of Seoul, Berlin, New York and Melbourne are apart from the essence of life and even people are invisible in the landscape.” Such works explain that the reality what Suh Yongsun has faced as an artist living in the same period, was not much different from the puzzled lives of people and the existence of human beings with communal destiny and their condition of life.

“This is never a mere literary narration. This is reality that awakens us to our surroundings and daily lives, and is the phenomenological and physical reality under our skins.” Suh’s perspective toward the world and life radiates tension that resembles a poem, while his quantitative volume has reached the level of possessing the breadth and depth of a saga

Ihn Bum Lee (Professor at Sangmyung University)

Suh Yongsun

New York subway riders waiting at the Union Square station, café-giers in Melbourne, and the environs of the Brandenburg Gate appear as subjects among thirty-six paintings and six sculptures by Suh Yongsun at the Hakgojae Gallery. The style is a mix of Cubism, Fuavism, and Expressionism – a sort of synthesis of early- to midmodern manifestations. Suh’s stubborn insistence on such stylistic choices stands apart from the fundamentally Westernized mainstream trends in modern Korean art, which has been dominated by minimal abstraction from the 1960s through the ‘80s, and since the ‘90s by installations, media art, and other typical contemporary practices.

Arriving on the scene in the early ‘80s, Suh has long been indifferent to current trends and thus has been able to focus on the basic issues of representation as a communicative and emotional maneuver. His interest in issues of minority, urbanization, and history has long been apparent in his painterly activities. Visa Project, 2002, concerns immigrants on the borders of nation-states, and Drawing and Thinking About Cheolam, 2001, is aimed at the resurrection of a deserted coal-mining region-both projects were undertaken after Suh joined the artist group HALARTEC. In numerous paintings and drawings concerning the over throw of the twelve-year-old King Danjong in the fifteenth century. Suh draws attention to the brutal deaths suffered by the loyal subjects who tried to defend the young king.

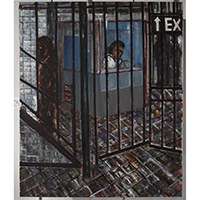

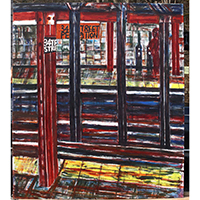

Suh Yongsun, People Waiting Subway at 14th Street Station, 2010,

acrylic on canvas, 56 1/2 x 90 3/4”.

In Suh’s most recent exhibition, the gridded background from the tiled lining of the subway station and the strong vertical and horizontal lines in People Waiting Subway at 14th Street Station, 2010, seem almost too rational for the dark and ominous depiction of four men, seated or standing on the bottom edge of the canvas, haphazardly looking away from each other, yet well-balanced enough to remind one of Seurat’s La Parade de Cirque(Circus Sideshow), 1887-88 .Subway – For Downtown, 2010, is characterized by the mostly gray •blue palette that vividly evokes the damp and metallic air of the underground and the frozen, seemingly archaic gestures of the riders on New York’s 6 train. The tense, almost abject expressions on the people in the subway series indicate the struggles of urban minorities. Suh uses the physical movement uptown and downtown as a metaphor for the movement up and down the capitalist class system, from the bourgeoisie of Manhattan to the working-class immigrants in the outer boroughs.

Painted during the artist’s stay in Berlin, Brandenburg Gate, 2006, shows the central image of the gate, in a view from above, obstructed by the heroic statue of a Soviet soldier ; set in the Tiergarten near the gate, the statue commemorates the sacrifice made in 1945 when the Red Army entered Berlin and Adolf Hitler committed suicide. Behind the statue and the gate, one sees a line sketch of the Reichstag. Amid these scenes, below the main group of images, is a depiction of a prisoner and guards at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, which Suh found in a newspaper while in Berlin. This juxtaposition of icons and associations from the artist’s inner life. Suh’s acute awareness of the anonymous other, especially those historically and socially victimized, is inscribed as a surging hopelessness in otherwise casual landscapes

Shinyong Chung(Art Forum)

The Discreet Charm of Suh Yong-sun's Art

Here, you see people. These people seem to be enduring their lives rather than enjoying them.

The eyes of some of them do not have pupils so their expressions are hard to be read, but all of them have seemingly blank faces on the surface behind which the burning flames in each mind are gushing out by way of different colors in their own individual aura. These are the people living in the world of Suh Yongsun’s painting.

Suh Yongsun, who is featured by National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea as the artist of the year 2009, is widely known for his series works in which the people in cities are depicted and for history paintings where historical incidents are visualized although he has dealt with a variety of themes such as figures, landscape, history, war and myth. It was in the early 1980’s mid 1980s he stared to produce history paintings and the ‘Urban People’ series. These works ruminate over the existential pain of the individuals who are caught in the vortex of history and the anxious minds of modern people who are living in the suffocating space of the expanding city. In Suh’s works, the problems of human existence are sublimated by way of his distinctive artistic languages in solid and constructive compositions and aggressive colors.

In this article, I intend to explain what makes the art of Suh original and to elucidate it in relation to where the interest or emotion of the viewer comes from. I certainly hope that this article is a ‘discreet’ writing that reveals the ‘discreet charm of Suh’s art,’ but, needless to say, it is the reader who decides whether my intention is achieved.

Regardless whether he intended or not, it would be difficult to refute that the works that deal with the stories of Danjong in Korean history of all his works demonstrate the originality of Suh most prominently. His ‘history paintings’ are different both form the typical history paintings such as those by Jacques-Louis David in which emphasized the attitude to accomplish historical missions whose importance was newly highlighted to the people at that times and from contemporary history paintings such as those of Leon Golub which deal overtly with the violence committed in today’s reality. Though impossible in reality, let us imagine a place where a large number of conventional history paintings are shown together. In this place, Suh’s series of history paintings would arrest one’s attention with their bewildering images like the skeleton that suddenly appears in The Ambassadors by Holbein.

In the passage of time flying as swift as an arrow, present reality scatters away at once into the past and becomes absent. When one can define history as the process of replacing with memories reality which so immediately enters into the state of absence, it can be said that history is too a kind of a symbolic order. Yet the realities in the period of King Danjong’s reign could not locate themselves within the official, symbolic order. For a while, the historical facts during the period had been documented under the title of ‘Prince Nohsan’s Diary’ instead of under the category of the authentic history. In the usual case, when a king passes away, the achievements of king are supposed to be written in the official records of his life, and his tomb is to have a tomb journal and a map of tomb, but in the case of Danjong, the official records of his doings during his lifetime were not documented during the time and even a formal tomb was not built for him.In the paintings of Suh, the incidents realted to Danjong are revealed as the real that was deported from the symbolic order of the official history and thus as a historical trauma which has been buried in the collective un conscious of Koreans as a traumatic memory.

In addition to the description of Suh’s paintings by the analogical use of Lancanian concepts, let us briefly examine the social implications of Suh’s paintings. To borrow the idea of Louis Althusser, what I have called the symbolic order of the official history above is an ideology. It is quite overwhelming to see how long the ideology of the winner in history, which prevented Danjong from being registered in the authentic history for a while, has continued its influence. How faithfully have such an ideology of the winner been reproduced in the TV dramas made by the mass media, to which Althusser referred as one of ‘the ideological state apparatuses’. And Suh puts on the brake, in the dimension of the individual, on the perspective of the winner inculcated one –sidedly by the drama produced by the ideological state apparatus.

Needless to say, the incidents occurred in relation to Danjong, especially the stories in which the Sayuksin(the six Martyred Loyalists)and the Sangyuksin (the Six royalists who survived) were involced, might be reduced to an edification through which one of the features of Confucian ideology of loyalty s reinforced. As a matter of fact, it was through the reevaluation of the stories hidden behind the authentic history and the improvement of historical remains that such kings of joseon as Sukjong, Yongjo and Jeongjo strengthened their ruling ideologies.

It is certain that such a feudalist ideology of monarch has become a relatively obsolete ideology however, from the propaganda paintings I which anachronistic ideas are lifelessly reiterated. Let us imagine that Suh’s themes are depicted in the Classicist mode like in the nationalist paintings that were actively made under the military regimes in the past. Then, it is obvious that those paintings would look like practical paintings whose purpose lies in the persuasion and instillation of ideology and which are thus somewhat unsatisfactory in terms of aesthetic qualities. But Suh employs an expressionstic mode for his works. This happens to remind one of Francis Bacon’s variations of Velzuquez’s portrait of Pope innocent X. Historical facts are transformed into the pains of individual beings involved in them.

Therby,” t can be said that my paintings are the improvisational and expressionist depictions of the objective historical facts on the basis of my own subjective interpretations,” says Suh.

The rhetoric of ‘the individual, ‘which is also implied in the use of the subjective interpretation of historical facts, is much more fortified by the reference to his own body through the indexical sign of expressionistic bruchstrokes. This is also another factor through which Suh’s paintings are distinguished form those history paintings usually registered in the passage/genealogy of the Realist tradition with strong purposes subordinate to ideas or dogmas.

On a method demonstrated by himself in the creation of a modernist painting which also possessed figurative elements, Bacon summarized in a phrase as follows: Try to make it resemblant. Yet only through a method that is accidental and is not resemblant. According to accumulate as it acts as certain modes of action and choice. And it is these marks and touches that transform a painting into a form that is recreated into a higher dimension by rescuing it form a simple composition that merely resembles the object to be painted. “First of all, I just make a line as I see it. When you make a wrong line, it is not wrong at all. Because that is a starting point. This line must perform a certain role when it meets another line, says Suh, and in this remark is revealed a logic corresponding to that of Bacon on the image made through the accumulation of indexical line drawings.

These expressionistic brushstrokes contribute to the disclosure of the condition of painting of two-dimensionality and its materiality in the course of modernization that painting took by pursuing its own nature. One can take the paintings of the COBRA artists as an example of the representative works that intended to reveal the property of painting as amteral through violent brushstrokes. The works of such COBRA artists as karel Apple are characterized by their strong emphasis on the materal attribute of painting and the maximization of the violence of the trace made by the artist on front of the pictorial surface. On the contrary, the paintings of Suh do not emphasize the material nature of painting as extremely as the COBRA participants did, and they take a moderate course while using violent brushstrokes as a methodology to deliver the themes rather than for the purpose of violent, emotional extrusion. The way of Suh’s brushwork resembles less the uncontrollable ejection of anarchism and nihilism than the powerful force which a master swordsman implicitly exhibited in his calligraphy, as exemplified by a figure in the film, Croching Tiger Hidden Dragon.

In giving form to the sufferings of a human being, Francis Bacon employed a grotesque and almost bizarre, formal distortion as well as expressionistic brushwork. Deleuze analyzed that Bacon utilized deformative transformation of forms in order to capture and depict the invisible force.

On the Contrary, Suh uses a very crude depiction of images to the extent that they look rather innocent. This stylistic feature extends the expressive potential of colors. He gives emphasis to the expressive possibility of liens and colors within the limited formal condition that appear tobe apparently rigid while saying that” … It is only that rich thought that is latent in it is not grasped by people. I do not think that the faces of the figures are blank. I admit it to the extent that the form of the painting contributes to their seemingly blankness. But when one pays more attention to the lines and colors, the thoughts in the paintings cannot be explained only through rigide forms. The apparent, rigid parts are in deed conspicuous, but there are many stories in them. I believe that people can hear them some day.”

To me, it seems that his emphasis on the potential of colors originates from his Oedipal impulse to overcome the modernist mode that the artists of the previous generation as elder artists or teachers employed. This psychological intent of Suh can be backed up by his remark of Korea in the late 1970s and further while I thought over Eastern art in general. I think I read an article about White Monochrome Paintings of the period and its relation to the white porcelains explains the underlying influence of such a sense upon the present period of Korea. Also, I think that Joseon’s sense of color has not been improved in the consciousness of contemporary needed to destroy the existing concept of color.” His urge to be liberated from the oppression of modernism that the standardized, modern urban space embodies is revealed also in this words,” “In the respect that excessive colors and brushstrokes can be used as the tools to express the urge to cope with the suppressed, urban culture, expressionist painting is related to the densely clustered space of modern urban architecture.” In addition, it seems that his Oedipal impulse to surpass the father figures in the field of art underlies his repetition compulsion of a tenacious inquiry into history painting, which one seldom finds among contemporary painters, and this is suggested also in his words in regard to the fact that his teachers participated in the production of nationalist paintings, “ There is a curious connection among the facts that Korean minimalist paintings, “There is a curious connection among the facts that Korean minimalist painting the state were produced and the Yusin Constitution was approved in the 1970s when Seoul was rapidly rebuilt as a modern, urban city. “ It might be that the artists, who were pursuing modernist abstraction as their own artistic aim, were psychologically traumatized by the forced circumstance in which they had to perform anachronic, artistic activities of making nationalist paintings under government control. And did not he intend to discover a cure for the psychological trauma his artistic teachers might have suffered by attempting to make aesthetic accomplishments in his history paintings?

The liberation of color was the artistic problem whose solution not only Suh but Bacon wanted to find. There is also a prominent difference as well as such a similarity shared by many of contemporary artists. The paintings of Bacon, which frequently used the form of a triptych, were produced in the manner through which isolation and discontinuation are enumerated, as emphasized also by the form. This characterizes all of Bacon’s paintings of the alienation and loneliness of modern people as well as his works in the formal frame of a triptych. In the paintings of Suh, on the contrary, although individual elements are separated two-dimensionally, they are reassembled within the interrelationship with one another so as to form the whole. It is due to this feature that Suh’s works can be differentiated from the painting of Western, Neo-expressionists to which his works are often compared.

Many critics have pointed out the influence of Neo-expressionism on the work of Suh by mentioning the restoration of figurativeness and narrative content, which were rejected by modernism, and the stylistic features of violent expression and intense colors . And Suh does not deny the stylistic influence of Neo-explanationism.

Let us compare Suh’s work to that Leon Golub was mentioned above as one of contemporary history painters. Apart from the aspects that they employ the expressionist mode to deal with historical contents and that they interpellate the lives of people that did not attract the attention of the world in the marginal region of history into the visible realm b transferring them to the arena of representation, Suh and Golub share a very concrete similarity that their frequent theme is ‘interrogation’. In the respect that it exposes the cold reality of violence that may be used somewhere in the world at this very moment, Golub’s Interrogation is different from Suh’s Interrogation which reflects upon the incidents that are distant from the present period to some extent. Also, there is a considerable difference in terms of subject matter and the form through which it is delivered. In the paintings of Golub, the background is almost eliminated and only the human beings are emphasized. In the works of Suh, however, the humans and the environment around them interact with each other as they compete with each other. Sometimes, buildings and spaces cut into the human figures, and at other times all these elements are jumbled up while overlapping one another. It seems that his modernological interest is realized in his representation of modern buildings represented through the form of the grid or the infrastructure of the city. In other words, it seems that his paintings portray the remains of the archeological inquiry into the modern

In some paintings of his, furthermore, the figures of the present and the past are blended with the remains and architectural environments of the past and the present.

When American Neo-expressionist Golub pays attention only to the human figures while eliminating the background, in the works of Anselm Kiefer, a leading European Neo-expressionist, on the contrary, the human figures are absent while leaving only space behind. Since the works of Suh persistently hold fast to his interest in depicting human beings, Suh’s work is greatly different from that of Kiefer despite that both of them deal with the themes related to history in the expressionist manner. At the same time though, they correspond to each other in the fact that they employ their own ways to put some sense of distance between their works and the viewers.

The paintings of Kiefer create some tension between themselves and the viewers through the dialectic of absorption and estrangement. That is to say, Kiefer’s works invite the viewers to the illusion of an enormous space and simultaneously they depict the empty and tumbledown space where human beings are absent and obtain a retrospective and reflective distance through the affectional effects. Suh’s paintings attract the viewers through their intense narrativity attained through the depiction of the relationship between human beings and space. The stories in them and the powerful expression of colors. At the same time, the viewers are continuously driven out by the isolated figures without mutual gaze exchange and the synthetiv and subjective reconstruction of the pictorial space whose emphasis is on two-dimensionality, and this allows them to gain a reflective distance. In regard to this, Suh explains, “Since the painted picture incident by emphasizing the two-dimensionality of the object secure the objective position of other words, while the viewers align their thoughts with the narrativity of the content depicted, their eyes are armed with some sense of distance with the help of the tension caused by two dimensionality.”

Meanwhile, the paintings of Georg Baselitz, an eminent painter who stands abreast with Kiefer, are differentiated from the works of Kiefer in that they concentrate less on space than on figures, objects and the parts of them. (Fig 2) Nonetheless, it is understood that the work of Kiefer pays its ultimate concentrated attention to visual symbols. In the long run, the works of both artists have something in common in the respect that they place the focus on metonymical motifs or specific objects within the world. On the contrary, Suh’s art is distinguished in the fact that it concerns with the relationship that those objects and figures form with their surroundings and the interaction between them.

In Suh’s paintings, the pictorial space is structured to have multi-layered levels, and sometimes the sidewalk stands up and the wall lies down so that they intersect and are combined with each other. The horizontal, two-dimensional plane is expressed vertically or a vertical plane is depicted horizontally, and thus many different planes are densely entwined not within the real space but within the space of thoughts restructured in the mind. This feature allows one to consider the paintings of Suh as an analogical model for text, since, according to Roland Barthes, the etymology of text is a woven textile. Therefore, “His picture plane is not a mere, transparent mirror that reflects exterior reality. It exists as both a mediator through which a work and reality interact with each other in a ‘chemical’ way and an arena of Gestalt to structure the picture plane.

Such Yong-sun unmistakably understands that the lively cultural conditions the ‘breaths of our lives’ is netted in the perceptional materials of daily experience and in the pictorial apparatuses, methods and materials.”

Means of public transportation, traffic signal systems such as a signal lamp, various kinds of signs, advertisements and so on are some of the sign systems that constantly come on and off while controlling and giving a signal to the human behaviors and movements in the city. In the depiction of the modern city, Suh often crossed those signs and signal systems, and that strengthens the textual characteristic of his works. “While transferring the narrative function to the viewers, the artist removed anything but the minimum cognitive faculties from the image”. And these “small clues help the viewers to recompose historical situations and to activate the emotional movements in the formative qualities of the works.” In the end, the artist “does not explain such a result through descriptive shapes and induces the viewers to interpret the image properly.” This quality as visual text is manifested also by the narrative complexity of the polyphonic unfolding of the stories expelled from the official history through the polyfocal figures.

The paintings of Suh as visual texts stimulate, therefore, a variety of interpretative actions and constantly extend the possibility to widen the rages of their meanings.

I have examined so far the factors that form and differentiate the artistic languages of Suh in terms of themes and methodologies. At the same time, I tried to explain how contemporaneity comes out from the works in which the artist concentrates his artistic capacity on the very concentinal mediums such as painting and sculpture. In fact, it can be said that the contemporaneous qualities of the visual languages the artist employs are mostly quite universal already. Nevertheless, the fact that he uses such considerably universalized visual languages does not damage much the peculiarity of the artistic world of the works. This is due to the fact that Suh does not ignore the close relationship between his themes and stylistic modes and the spatial and temporal environments around himself such as climates and history. That is to say, it is because he produces his artistic results by applying the logic that he discovered through his tenacious inquiry into the close relationship of the spatial and temporal environments to those visual languages.

Under the disarrayed circumstance of the contemporary art scene in which depthless and superficial artistic plays are rampant and step into the limelight, Suh has built his artistic realm through prudent and in –depth study and inquiry on the basis of humanistic research and retrospection into his themes, and this artistic attitude of Suh is not easily found in the contemporary art scene and thus set an good example for many artists.

In this exhibition, Suh Yong-sun, who does not let himself swept along by the currents of the times and continues to ponder upon the authenticity of an artist, unfolds the moments of exceptional significances captured in his eyes in the long stretch of human history from the ancient to the present. The monumental panoramas of human history force one to cast grave and sincere reflection upon the meaning of human existence.

Kim Kyoung -woon (Curator at National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea)